Ghana’s space scientists are facing a growing crisis, not from the stars, but right here on the ground.

The Ghana Radio Astronomy Observatory, a critical research facility, is being swallowed by land encroachment, threatening years of scientific progress.

“The initial land was 165 acres. It came to 75. Now we are having less than 30,” says Dr. Proven Adzri Emmanuel who is the manager of the Ghana Radio Astronomy Observatory. “This facility is worth over $12-15 million, yet we are losing it bit by bit.”

The Ghana Radio Astronomy Observatory (GRAO) is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa, apart from South Africa. The site has a 32-meter radio telescope, a 16-meter telescope, and a 9-meter telescope. The scientists converted a redundant telecoms instrument into a functioning Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) radio telescope.

It is part of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project across the African continent. That is all threatened now.

The encroachment isn’t just a land issue—it’s disrupting critical radio signals used for space research. “People around us are producing radio frequency interference (RFI), and that background noise is affecting our data,” Dr. Proven warns.

According to Dr Provens, this frequency is “coming from the transmitting devices. We have our mobile phones, our microwave, our transmitters in several devices that are all around here, they are just feeding into it. So in terms of interference, we are doing very, very badly.”

Deputy Director, Ghana Space Science and Technology Institute, Dr. Theophilus Ansah Narh, stressed the interference is slowly squeezing them out.

“This is our project site. And one of the challenges that we are facing is the heavy encroachment. And not only that, it is affecting the science that we are actually doing,” said Dr. Theophilus Ansah Narh

But this is just one of the challenges facing Ghana’s space science community.

Tracking Ghana’s Vanishing Forests

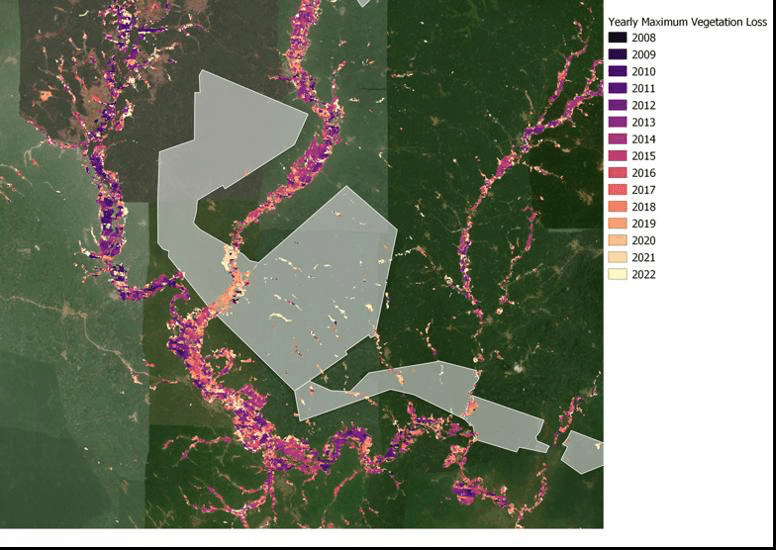

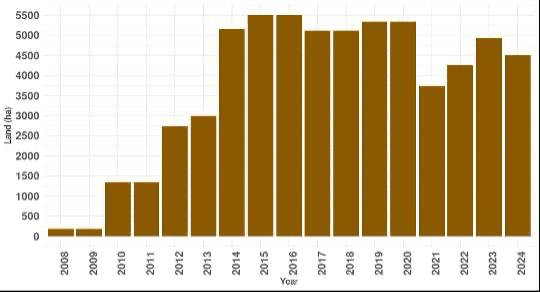

Despite the teething challenges, scientists at the Ghana Space Science and Technology Institute have turned their attention to another crisis: the country’s disappearing forests and polluted rivers. For years, Ghana struggled to measure the scale of destruction caused by mining, both legal and illegal. That changed in 2023 when space scientists used satellite technology to quantify the damage.

We are losing the equivalent of 23 football fields of forest cover every day to mining in general.

“Between 2007 and 2023, we’ve lost almost 55,000 hectares of land,” reveals Dr. Joseph Bremang Tandoh. He is the Director of the Ghana Space Science and Technology Institute. “We did it using satellite images—comparing snapshots from 2007, 2008, and beyond to track the land being lost.”

A year later, the situation had worsened. Manager of the Remote Sensing and Climate Center, Dr. Kofi Asare explained the conversation rate has spiked.

“A little over 59,000 hectares of land has now been converted to mining, equivalent to 84,000 football fields. From 2015 to 2020, mining expansion jumped by 72%. But from 2020 to 2022, it surged by a staggering 135%”.

The Western, Western North, Eastern, and Central Regions have been hit hardest, with forests being cleared at an alarming rate. But it’s not just trees—Ghana’s rivers, once a source of clean water, are now choked with toxic waste.

Space Science to the Rescue

To combat this, Ghana’s scientists have developed a way to track water pollution remotely.

“We monitor turbidity—how murky the water is—using satellites,” says Dr. Tandoh.

“Instead of sending people to inspect entire riverbanks, we take satellite images to estimate water quality. The technology allows us to monitor changes in real-time.”

Beyond tracking environmental damage, space scientists are also applying satellite technology to food security, developing algorithms to estimate farm yields using images of crops and soil conditions.

Ghana’s Space Science at a Crossroads

Despite these breakthroughs, Ghana’s space program is falling behind its African counterparts. Unlike Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt, which have multiple satellites in orbit, Ghana currently has none.

“We need to own our own satellite—built by Ghanaians, for Ghanaians,” Dr. Tandoh insists.

“Nigeria has about seven satellites. South Africa has launched nearly 13. Even Rwanda and Angola have satellites. But Ghana? As of now, we have none.”

With increasing encroachment, environmental devastation, and a lack of investment in space technology, Ghana’s scientific future is at risk. The question now is: will the country take action before it’s too late?